How to build transit: America’s forgotten streetcars can save us

The US once boasted the best streetcar systems in the world. We can learn a thing or two about public transit funding and procurement.

An inadequate current state of affairs

The way we fund and build public transit in North America isn’t working.

The US routinely breaks records for how expensive a piece of track can possibly be, while Canada builds that track - then refuses to open it (I'm looking at you Eglinton)

So how did things get this bad?

It all starts with how projects are funded. Money either comes from the government - or the private sector.

The biggest problem with government funding is unpredictability. Transit takes a long time to build, far beyond the time frame of annual budgets or re-election cycles.

Hamilton, Ontario gives us a great example of how things can go wrong. In 2015, the Ontario government agreed to fund a new LRT - only to decide in 2019 that “nope, we don’t really want to do that anymore” and withdrew their funding, effectively terminating the project.

They then decided that an LRT would actually be a pretty good idea 🤷, so the project was revived in 2021 with help from the federal government.

Political volatility makes relying on government funding a surefire way to make sure something doesn’t get built on time - or at all.

But it’s not like the alternative is perfect either. Nowadays, private money usually enters infrastructure projects through a Public-Private Partnership, or P3 agreement. This money typically comes from large institutional investors like pension funds or banks.

The US Department of Transportation explains it like this:

One of the primary motivations for a P3 procurement is the ability to use private capital to implement much-needed projects in the absence of—or delayed availability of—adequate public funding and/or to advance future project revenues.

which is a fancy way of saying: governments don’t have enough money for the high upfront costs of infrastructure projects today, so get the private sector to front the cost in return for a steady stream of money in the future, like a higher percentage of the fare revenue from a new subway line.

There’s way more nuance to this concept, but there’s one central truth behind P3 - transit by itself does not generate the financial returns needed to attract private capital, so P3 agreements have all sorts of guardrails regarding project risk and future revenues, creating an attractive situation for private players.

While theoretically sound, these incentives and risk allocations add up to a very complex agreement, very quickly.

It’s come back to haunt projects like the Ottawa LRT, where the city offloaded the geotechnical risk of the project as part of that specific P3 agreement.

This saved the city (and taxpayers) $100 million when a sinkhole swallowed up a street and it had to be covered by the private party as it constituted “geotechnical risk”. A win, right?

Not exactly. You see, it turns out that this specific P3 agreement also gave the city “limited insight or control” over the project. When issues inevitably arose, the City insisted on “enforcing its contractural rights”, creating an “adversarial relationship” that fuelled numerous delays and cost overruns.

These findings all came from OLRT public inquiry report, a 644-page document informed by 90 interviews and 19 days of public hearings over one year of work - all to investigate what went so terribly wrong with the project.

I’m not trying to discredit P3, by the way. There’s actually decent evidence that P3 outperforms traditional public-only procurement, with one study finding that traditional projects in Canada saw average delays of 428 days and cost overruns of 46%, while P3s were only delayed by 203 days and over budget by 22%.

But that’s exactly the problem. The latter is your “better” option.

A radical model from history

Which brings us to the forgotten streetcars.

From the 1820s onward for over a century, streetcars dominated the transit landscape, starting as horse-powered but culminating in comprehensive electrified systems across pretty much every city in the US.

What’s different is that most of these old systems were completely built and operated by private actors.

That’s right. No transit agencies, no public consultations - just pure, unfettered capitalism 🇺🇸

There were 2 main reasons for this:

- One: some cities would give companies the right to operate a transit monopoly if they’d build the system as well. Transit wasn’t such a financial black hole back then as it is now, so this revenue guarantee was often good enough.

- Two, and this is the really important one: if you were a private company that owned or developed land, it often made sense to build transit to increase the accessibility and therefore the value of your land.

Since cars weren’t yet mainstream, many developers built transit systems - essentially at a loss - in order to increase accessibility to the new suburbs they were building, growing the value of their own land as a result.

And a side note: because these suburbs were by definition built around transit lines, they’re not the sprawling, single-family housing suburbs you probably have in mind. “Streetcar suburbs” were dense, walkable, multi-use neighbourhoods that -surprise surprise - remain some of the most desirable areas in cities today.

Case studies 🤓

A few examples really illustrate this relationship between real estate and transit.

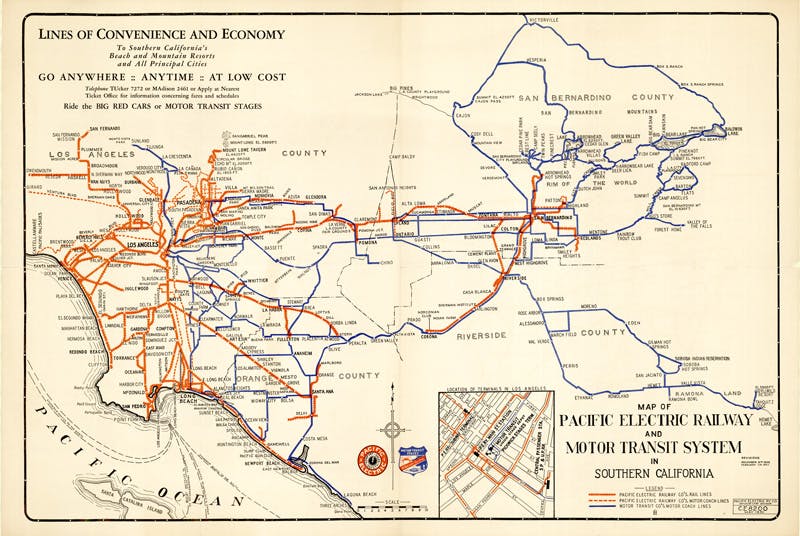

LA may be a traffic hellhole today, but they used to have 20 streetcar lines through the downtown core - complementing an interurban network spanning over 1,000 miles to places like San Bernardino and Orange County.

The principal architect behind this was Henry Huntington, a real estate and railroad magnate who moved to California and decided to play Cities Skylines in real life. Huntington is the main reason why places like Redondo Beach and - well - Huntington Beach even exist today.

As part of the gameplay, he aggressively built up 2 rail powerhouses: the Los Angeles Railway with “yellow cars”, and the Pacific Electric Railway with “red cars”.

These systems were “unprofitable in and of themselves”, but “grew into such an extensive system in large part because he needed them to take newly minted Angelenos out to far-flung tracts where they could purchase a lot of their own – from the massively land-owning Huntington himself.”

This not only tripled the population of LA, but also netted Huntington’s businesses tens of millions of dollars in appreciating land values.

Now, given that Huntington only did this in order to make a f*ckton of money, we probably shouldn’t blindly emulate what he did.

But we should pay attention to the fact that building transit - of all things - was the best way for him to make that money.

A similar story played out in Arizona.

At its peak, the Phoenix Street Railway boasted over 30 miles of track across 6 lines.

The source of the midlife crisis behind this scheme was Moses Hazeltine Sherman, a teacher who probably realised that he could make more money doing something else, so he built the Arizona Canal, started the Valley Bank of Phoenix, and bought enough real estate to become the largest taxpayer in the city.

He also founded the Phoenix Street Railway, which like Huntington’s network in LA, wasn’t all that profitable - but it wasn’t ever supposed to be.

With fares of one nickel, at least in the beginning, the railway’s only purpose was to make it easy to get to that real estate that Sherman owned in the still-faraway Salt River Valley area.

But it couldn’t last forever. Sherman ended up selling the system to the city in 1925 as growth naturally slowed, but by that point it had already served its purpose of building up these remote suburbs - lining Sherman’s pockets in the process.The city maintained the system for several more decades - until the inexorable rise of the automobile finally rendered the setup too financially infeasible.

And this is a good place to dive deeper into the automobile, because it’s really what shut this whole thing down.

The downfall - by the car and the budget

Recall that what made streetcars financially feasible was their benefits to other business ventures, like appreciating real estate.

This dynamic relied on one key fact: streetcars were the best way to move lots of people at reasonable cost.

That wasn’t the case after anymore after the car appeared - blowing up the foundation [sync with blow up animation] of what made streetcars financially viable in the first place.

We’ll get to exactly why in a second, but in the meantime, cars had a more immediate impact on roads: they took up a lot of space.

Only 10% of the population needed to drive before congestion got bad enough that streetcars started missing schedules.

In LA specifically, over 160,000 cars were clogging streets by the 1920s, leading to hourlong delays and drastically increasing accidents.

Even getting on streetcars became dangerous - they would run down the centre of a street, so passengers had to cross at least one lane of traffic.

But what really did it for streetcars wasn’t any free market phenomenon, if such a thing can exist. It was things like the Federal Highway Act, WW2, and the 1956 Interstate Act.

The streetcar was no longer the best way to move people around cheaply. Continued government support made the automobile cheaper - cheap from the perspective of land developers who had previously built their own transit systems.

Once it was clear that the government would bankroll car infrastructure, developers didn’t have to worry anymore about increasing accessibility to their faraway plots of land. Since the public could just use roads built and maintained by the government, why would anyone - let alone profit-driven private companies - build transit to compete?

And that’s the key: this wasn’t necessarily the result of cars, but policy.

What we can learn today

Every system is perfectly designed to get the results that it does.

The legacy of streetcars in America proves that private players are not inherently wedded to either cars or transit - or flying taxis or whatever technology you want.

Private players seek profit - and respond to market incentives along the way.

There’s really only 2 options for governments who are serious about building more transit: pay for it yourself, or create the right environment to use the resources of the private sector - fully.

We’ve seen that with the correct incentives, private companies will be clamouring to build transit so fast that you’ll have a whole other set of problems.

But specifically for today: if governments want to attract private investment without punitive sweeteners, or simply make transit less of a financial black hole for themselves to build, transit and private cars need to be on a more level playing field. You can’t pour money into one mode for decades and be surprised when the other one doesn’t work.

I won’t get too deep into the benefits of transit and urban development, but I will say this: transit accessibility still increases land value, perhaps more so today than ever before. Some places take full advantage of this, like Hong Kong’s unique setup with the MTR subway system, but it’s a concept that’s been largely ignored in North America.

One final note

One final note: this video is not a case for the full privatisation of transit.

A private approach is great for building new systems quickly, but not so much to maintain them in a measured or equitable manner.

This video is an exploration of just one possible solution to the impossible question of how we can fund more public transit. And with the need for better transit so painfully obvious across North America, we’re going to need all the solutions we can get.

Why not start by looking at history?