How American Airlines weaponised data

The history of SABRE, yield management, and modern airline economics as we know it.

Context

The 20 years following the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 were carnage. What had hitherto been a cozy, gentlemanly industry was almost overnight replaced by a fragmented bloodbath.

Two major changes were the significant dulling of restrictions on low pricing and new routes; prior to deregulation, these competitive acts were all but banned by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB).

It’s tempting to think that before deregulation, much like the pretense to Avatar, all airlines lived together in harmony. This could not have been further from the truth. Airlines may have been prohibited from competing on traditional measures like price, but that only encouraged more extreme, outlandish forms of competition. Flight attendants are an easy example; having young, arresting women serve you on long flights was as much a competitive selling point as was serving filet mignon and lobster.

In this way, the Deregulation Act was inevitable; airlines were already competing on everything but price. The oversight of the CAB was seen as excessive, and a confluence of political forces — including a new President Carter looking for a quick win — ensured that 1978 would close with a bang. It was the most radical shakeup of the industry since the Spoils Conference of 1930 that created the Big 4 of American, Eastern, TWA, and United, and — ironically — brought such heavy regulation in the first place. History really is funny.

Key Players

Our duel takes place against this backdrop in 1985 — less than a decade after deregulation.

In one corner we have American Airlines, a veritable giant that claimed every few years to be the largest carrier in the world. In reality, it didn’t matter whether American was 1st or 2nd — they were large, they were growing, and they were a bully. Fiery CEO Bob Crandall intended it as such, launching his vaunted “Growth Plan” a few years prior that unequivocally placed American on a path towards dominating the entire airline industry.

The Growth Plan — like Crandall — was as diabolical as it was ingenious. It rested on controversial “b-scale” wages that systematically paid new employees less than existing staff, part of an effort to bring costs in line with low-cost “upstarts” like New York Air. Crandall cleverly convinced American’s unions to sacrifice their staunch collectivism, no easy feat, by ensuring that incumbent union members would benefit immensely from the scheme.

Existing employees retain their sky-high wages, and a growing airline would give them easy promotion opportunities. Everyone could see that these benefits were mortgaged against future employees, but did it matter? The incumbents were the ones who would vote, after all.

I honestly hadn’t heard of People Express before writing this

“The Southwest Airlines philosophy but without the brains of Southwest” — American Airlines on People Express

Their challenger was People Express, the antithesis of American and one of the pesky upstarts that unabashedly emulated Southwest’s no-frills model. CEO Don Burr launched People Express in 1981 to fill a growing void in the Northeast; the 1970s energy crisis had turned the Steel Belt into rust, rendering full-service flights unpopular and unprofitable.

With legacy carriers like American and United redeploying their fleets to serve more lucrative markets, Burr jumped at the opportunity to dethrone languid regional incumbents like USAir.

Despite the airline’s humble beginnings, Burr had no intentions of staying small. People Express started by serving 2nd-tier destinations like Columbus and Buffalo from Newark, a much cheaper hub than LaGuardia and JFK, but they soon began picking fights with the big boys.

Burr inexplicably began pushing into Chicago O’Hare and Detroit — United and American strongholds, respectively. In a prescient remark, American’s pricing department described People Express as having “the Southwest Airlines philosophy but without the brains of Southwest”.

They weren’t wrong. Southwest’s expansion was deliberate and disciplined, the polar opposite of Burr’s pell-mell expansion fueled by big dreams and cheap debt.

Buildup

Low cost carriers + 747s = definitely the 1980s

The face-off was years in the making. Crandall had grown increasingly apprehensive about the unfettered growth of Southwest imitators, and no carrier concerned him more than Don Burr’s People Express. By 1985, Burr’s goals were looking dangerously ambitious for American; the upstart even had transatlantic routes to London Gatwick with a Boeing 747, the undisputed hallmark of commercial aviation power.

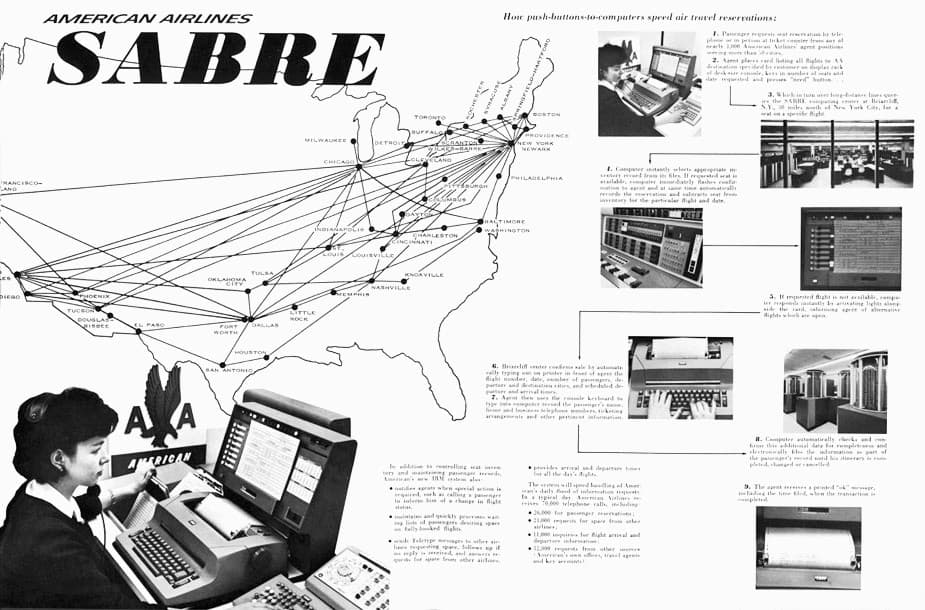

Fortunately for American, they possessed an asset that few airlines could afford: a proprietary computerised reservation system. Only the rest of the “Big 4” — United, TWA, and Eastern — along with Pan Am and Delta could say the same.

These systems had innumerable defensive and offensive uses, many of which were difficult to initially discern. Apart from the internal efficiency gains of moving away from manual ledgers and punch cards, several potential offensive capabilities soon became apparent.

Recall that this was the era before Google Flights and Expedia, when travel agents were still the undisputed gatekeepers to flying. Giving travel agents direct access to airlines’ reservation systems, and making sure that agents used one system exclusively, meant that these individual airlines controlled which flights could be booked by travel agents.

Like every high-tech invention in the U.S., SABRE had Cold War roots — Photo by IBM

It didn’t take long for American to figure this out. They invested heavily in their ominous-sounding SABRE reservation system, launching a dual-pronged effort to push the boundaries of computing power whilst convincing the nation’s travel agents to use SABRE and SABRE only.

Of course, the other airline giants were doing the same. Armed with systems like PARS, DATAS, and SystemOne, airlines began pushing competitors’ flights to the bottom of booking screens seen by travel agents. Retaliation often came in the form of equivalent computerised discrimination or, from carriers who didn’t control the screens, deep fare cuts that devastated everyone’s bottom line.

Crandall knew that these tit-for-tat skirmishes were missing the big picture, however. Only losers would result from these discount-for-discount schemes, and actively censoring competing flights on a supposedly “open” reservation platform was bordering on illegal. American needed an edge, and SABRE was about to give it to them.

Showdown

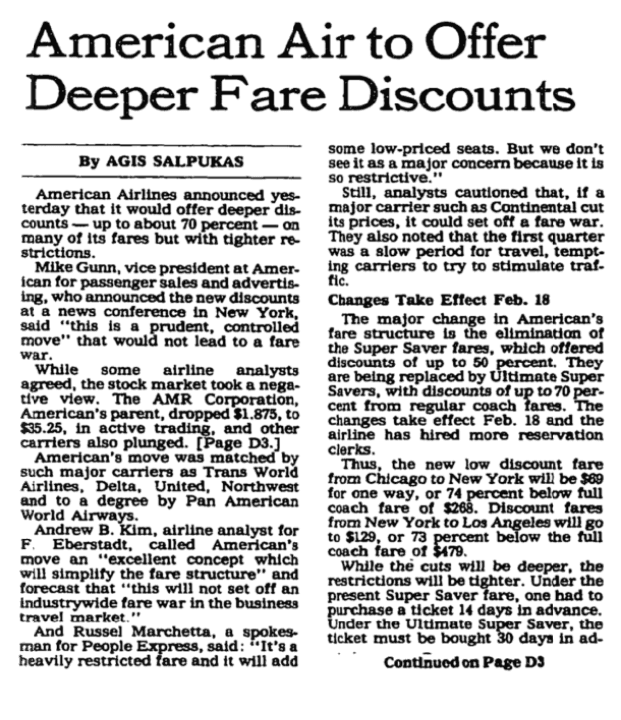

It was only a matter of time before American and People Express came head to head. On January 17, 1985, the inevitable arrived. American revealed their Ultimate Super Saver fares and brought the sky down on People Express.

The New York Times (January 18, 1985)

The numbers were staggering: Chicago to L.A. for $109, down from $403. Chicago to Dallas for $79, down from $265. All one-way trips between the 92 cities served by American would be available from $39 to $129. People Express could only watch in horror as their own $99 fares were suddenly deemed uncompetitive.

By mid-1985, People Express was deeply in the red, while American somehow seemed unfazed by their massive self-inflicted price cuts. Burr was running out of options and, in true 1980s Wall Street Raider fashion, addressed the issue by acquiring the struggling Frontier Airlines in October. (?)

When in doubt, acquire another airline

Unsurprisingly, the acquisition didn’t save People Express. The awkward, conjoined airlines limped on for another year and a bit, finally sputtering to the end on February 1st, 1987. Crandall had succeeded.

From the outset, this may seem like a classic case of “entrenched industry giant crushes small startup”, but the reality is a little more complex. Like the title of the article suggests, American Airlines had an unanswerable weapon at their disposal: data.

One hitherto unmentioned benefit of SABRE was the 20+ years of data collected since the system came online in 1964. American had access to precious, precise information like how often leisure travellers to the West Coast would be no-shows, or how many days in advance business travellers from New York to Chicago would book their flights.

This data allowed American’s “yield management” team, the first of its kind, to give meaningful recommendations on how much to charge for which seats.

Yield management was the silver bullet, at least before the competition caught on. It meant that American could sell seats on the same flight at different prices to optimise profits.

This wasn’t a new practice — airlines had been offering variable pricing for years — but SABRE data turned guesswork into a calculation.

American could price tickets such that every seat on every flight was bringing in the maximum dollar amount that each customer was willing to pay, giving them the flexibility to take down People Express.

People Express had no counterattack; they didn’t have a computerised reservation system, much less 20 years of data to analyse. To add insult to injury, one of People Express’ selling points had been a simplified fare structure where every seat was the same price. They were hamstrung.

To better illustrate the advantage that yield management gave American, consider the following example:

- Both American and People Express could advertise $99 fares, but American only sold the absolute minimum number of $99 seats it needed to in order to fill their planes; the remaining seats would be priced towards higher-paying passengers according to the predicted prices that they would be willing to pay.

- By contrast, every seat on People Express was $99.

- Even if People Express discarded their uniform price structure, and if some passengers were willing to pay more than $99, the airline had no way of calculating how many seats to sell at higher prices. The average fare on American flights therefore turned out to be much higher than $99, whereas seats on People Express would be hard pressed to break the $99 range.

Crandall was playing by a different set of rules. He could keep the promotion on for as long as it took to put People Express out of business, because American wasn’t actually selling every ticket at $99. Burr knew this, but he was powerless to stop it.

Conclusion

Yield management has since evolved to become an integral component of modern airline operations. Nearly every airline prices their seats differently based on an arcane set of criteria, more often than not taking into account your browser cookies and personal data.

It isn’t uncommon to hear people yearn for the “golden days” of aviation before deregulation. By extension, yield management sometimes takes the blame for bringing unnecessarily complication and even adding deceit to the passenger experience. That may be partly true, but keep 2 things in mind:

- $99 in 1985 is worth over $230 in 2020.

- In 2020, American Airlines flies from New York to L.A. for $149.

The Boeing 737 — Photo by Boeing

I came across this story while reading Petzinger Jr.’s Hard Landing, an incredibly engaging book that covers the chaos following airline deregulation in America.

Yield management was not remotely near the primary focus of the book, but as someone who 1) studies statistics and CS and 2) wants to join the airline industry at some point, general revenue management will undoubtedly be a potential entry point.

Writing this piece was therefore immensely valuable to me, letting me delve deeper into the field. I can only hope that you also learnt something along the way!

References

- Hard Landing: The Epic Contest for Power and Profits That Plunged the Airlines into Chaos — Thomas Petzinger Jr.

- American Air to offer deeper fare discounts — The New York Times, 1985

- Major airlines play cutthroat with fares — Chicago Tribune, 1985

- American Airlines’ plan to undercut discount carriers by slashing rates — AP, 1985