How Canada's Jetliner (almost) beat Boeing

The history of the Avro Jetliner, a tribute to its premature death, and how it could've catapulted Canada into the future.

Our world grew much smaller after 1949. The de Havilland Comet teased at the technological and business potential of civil jet transports, boasting 4 turbojet engines that allowed it to literally fly above the piston-powered competition. Though it would never achieve commercial feasibility, the Comet captured imaginations as it tore through all conceivable civil aviation records.

It wouldn’t be alone for long. 13 days after the Comet’s first flight, another civilian aircraft thundered into the skies off the strength of 4 Rolls-Royce Derwent turbojets. A mere 8 months later this same plane would make the first international jet transport flight in North America, a record-breaking 58-minute dash between New York City and Toronto. With unparalleled speed and passenger comfort, multiple airlines, including Howard Hughes’ TWA, saw the potential to shrink the continent. Even the U.S. Air Force outlined a desire to purchase 12 of these jets.

This mystery plane wasn’t the Boeing 707, a fine aircraft that would fly over 8 years later. It wasn’t even American. The aptly named Avro Jetliner was a Canadian jet that, at least briefly, appeared poised to dominate the North American market.

No aircraft could equal its performance on short, intercity routes, the kind that strung together the Eastern Seaboard. No aircraft would come close for nearly a decade, making it Avro’s game to lose.

And they lost.

The Jetliner never made it to the market, and only a single prototype was ever flown. Despite handling years of rigorous testing, it was broken up in 1956 — a full year before the Boeing 707 ever flew. Like so many stories in aviation, the Jetliner’s demise was more political than technological, more economic than scientific, and more consequential for Canada than many foresaw.

This article is a story about a little jet that, 70 years ago, could have catapulted Canada into the future.

Aerial Supremacy

To understand how greatly the Jetliner outclassed its competition, you first need to study the competition. The Jetliner’s 1,500 nautical mile range was tailored for Canadian demands, such as the Triangular Route linking Toronto, Montreal, and New York City. These routes were filled by a litany of propeller-driven airliners, including the venerable Douglas DC-4 and Lockheed Constellation.

The Lockheed Constellation — Image by Lockheed Martin Media Relations

Although they were fine aircraft, and some even featured pressurised cabins, none could match the speed and ceiling of the Jetliner. Flying higher avoids turbulent air, giving the Jetliner a smoother and faster ride. Her cruise speeds hovered around 400 mph, and her envelope was pushed to 500 mph during testing. She could nearly halve the time on the Toronto-New York route.

The Jetliner handled well on takeoffs and landings, not requiring excess runway length as many had expected with such unproven technology. Equally important were design features like rounded windows, avoiding a key flaw that doomed the Comet. The incredible improvement on noise and vibration also produced several stories; additional vibrators were fitted to certain instrument needles to prevent them from sticking, whilst during one promotional flight the Jetliner’s passengers could hear a nearby media plane’s propellers over its own turbojets.

“the Avro Jetliner [was] further advanced than the Comet… the American market [was] wide open for it”

U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administrator Delos W. Rentzel heaped this praise on the Jetliner in a 1949 interview with Maclean’s. (I personally love this particular article’s name: OUR ALL-OUT GAMBLE FOR JET SUPREMACY)

With widespread consensus on the Jetliner’s immense potential, why did it never enter service? The answer lies within another question:

Why was the Jetliner created in the first place?

Turbulent Growth

On the surface, the Jetliner was designed to meet passenger aircraft demands from Trans Canada Airlines (TCA), a Crown Corporation. Yet the plane was also an attempt at establishing a Canadian foothold in the nascent civil aviation industry.

The benefits were easy to see; high-tech industries associated with aircraft development would attract global talent and business. Canada could then retain the people and their technology, reducing dependence on foreign military technology.

You could definitely frame the situation as being fairly important, but judging by what happened, you’d think that not many people did.

The Canadian government initially supported the project, even stepping in with a $1.5 million bailout when the Jetliner was on life support in 1947. However, this intimate relationship ultimately choked the program. TCA, and by extension the Canadian government, was the Jetliner’s largest shareholder and only customer. It was as close to a one-way relationship as you’d get; Avro needed TCA and held no bargaining power.

When TCA disagreed with Avro over contract terms in 1947, TCA simply pulled out. It turns out that depending on parties with secondary, often politically charged agendas isn’t always conducive to success.

The Jetliner touring New York City — Image by the Aerospace Heritage Foundation of Canada

Sensing American interest, Avro launched promotional flights in the states. Miami-based National Airlines and Howard Hughes’ Trans World Airlines were amongst those who expressed a serious desire to operate the Jetliner, with Hughes even offering to produce the plane under license with Convair due to the perception of limited Avro resources. The U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Weapons Board went as far as approving the purchase of 12 Jetliners, intending to exploit the plane’s versatility in roles such as mid-air refuelling.

In a testament to the plane’s reliability, the American Civil Aeronautics Administration stated that the Jetliner would likely be granted a Certificate of Airworthiness, while the Comet would not.

It wouldn’t matter. The Jetliner would never need such a certificate.

Aborted Takeoff

You probably couldn’t go a decade during the 20th century without having a war erupt somewhere. The 1950s was no different; just 5 years after the guns of WWII fell silent, the Korean War beckoned. Largely relegated to producing other countries’ aircraft designs during the Second World War, Canadian leadership wanted the country to play a bigger role this time around.

2 CF-100 Canuck Fighters, double the number of Jetliners ever built — Image by RCAF

Fortunately for them, Avro already had a jet fighter designed and ready for production: the CF-100 Canuck. Unfortunately for Avro, the Jetliner played no part in Canada’s Korean War plans. A 1951 Canadian Department of National Defense memo by Air Vice Marshal D.M. Smith stated that:

“it was never our intention that if this aircraft was required that it would be built by A.V. Roe (Avro). They are fully committed now with their CF-100 (Canuck)”.

The story gets muddled at this point. Much of this confusion is owed to C.D. Howe, known affectionately as the “Minister of Everything”; his real post-war job was serving as Minister of Reconstruction. He was a driving figure from the Jetliner’s birth with TCA through to its painful death, making a plethora of short-sighted decisions that still don’t have conclusive explanations.

For example, despite granting the aforementioned $1.5 million loan, Howe’s response to National Airlines’ interest in the Jetliner was “no way”. This was revealed in an interview with Avro Canada’s Chief Design Engineer, Jim Floyd, who also said that:

“C.D. Howe at that time was God as far as the aircraft industry was concerned”.

Howe was likely also aware of the USAF’s official interest in the Jetliner, yet there is no evidence that Avro was ever informed.

Why did Howe actively suppress the Jetliner? The threat of escalation with the Korean War cannot be ignored, but neither can Howe’s personal interests. For example, Howe had spent considerable effort clearing airspace for the Canadair North Star, a Douglas DC-4 variant built specifically for TCA. The piston-powered North Star was no match for the Jetliner, yet 20 aircraft had already been earmarked for TCA on Howe’s orders. This commitment undoubtedly hamstrung the airline’s ability to field the Jetliner.

The upper ranks of governance also viewed the Jetliner unfavourably. The aforementioned Department of National Defense memo claimed that:

“the C102 (Jetliner) is nothing like as far advanced as advertised by the company… we would be unwise at this time to try and sell it at all”.

TCA’s Director of Engineering, J.T. Dyment, later added in 1951 that “time had run out on the aircraft now. The original lead gained by the prototype has been cut… because competitive aircraft are now on the way”. In hindsight, the second statement was untrue; the next regional jet produced anywhere would be the French Sud Aviation Caravelle. The Caravelle’s first flight would come in 1955, 4 years after Dyment was under the impression that the Jetliner’s lead had already become obsolete.

The Sud-Aviation SE 210 Caravelle — Image by Sud Aviation

The lack of Jetliner flights makes it slightly difficult to verify whether performance was truly poor, but veritable doubt evidently existed within government leadership. Perhaps Howe and other influential figures felt that working on the Jetliner would draw resources away from the Canuck fighter, undermining Canada’s opportunity to demonstrate her technological prowess on the global stage of war.

Ironically, the Jetliner would have been a much more impressive display of such expertise. Serving regional North American routes would have captivated the jet-fueled imaginations of ordinary citizens across the world’s largest economy.

On an upsetting note, Jim Floyd stated that the Jetliner could have easily been produced alongside a growing number of Canuck fighters. It is unlikely that decision makers were unaware of Floyd’s views and the widespread interest for the Jetliner, adding to the perplexity behind her eventual execution.

At this point, I’ll admit that I still haven’t found a definitive answer to why the Jetliner was cancelled. Hopefully this information helps you form your own opinions, because this story is far too complex for me to come up with that single answer any time soon.

The Cost to Canada

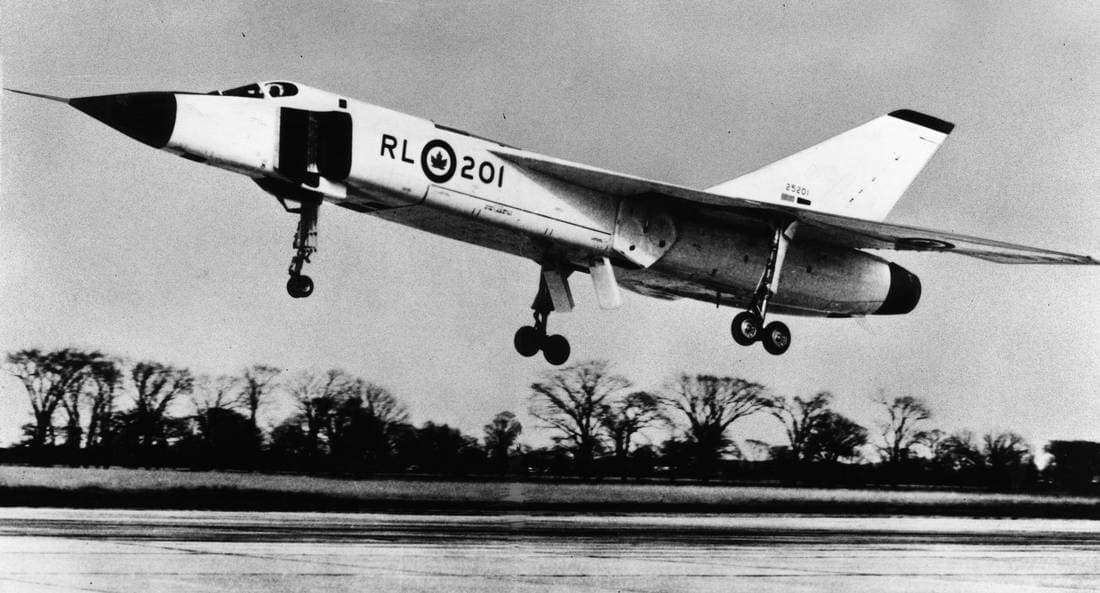

The Avro CF-105 Arrow Interceptor, another doomed creation — Image by Avro Canada

It would be foolish to disregard the potential gains from an effective Jetliner program.

Strong operating economics, passenger comfort, and the novelty of jet travel would have helped the Jetliner capture many short-haul routes hitherto unserved by jets.

At the time, this meant every short-haul route in the world.

Granted, many airlines preferred the proven reliability of propellers, but it wasn’t inconceivable for the Jetliner to be welcomed into the North American market — at the very least.

This popularity would have placed Canada firmly at the forefront of technological innovation, helping to draw talent from overseas and perpetuating the accumulation of knowledge. The economic benefits from attracting talented individuals go without saying; the families they bring help incentivise the development of accompanying industries like finance, education, and legal services.

Equally salient is how Avro Canada was robbed of their best opportunity to pierce the nascent civil aviation market. The latter half of the 20th century was an aviation free-for-all; modern-day bullies like Boeing and Airbus either didn’t exist or simply weren’t strong enough to control the market in the way they currently do. Success for the Jetliner could have encouraged Avro to expand their civil offerings, reducing dependence on military contracts that were — and always will be — vulnerable to political whims.

It was this dependence that killed Avro after another saga with the Arrow interceptor, although that truly is another story.

Finally, the upside is so tantalising because only our imagination can constrain it. Imagine if the Jetliner became an instant hit. Avro then creates an intercontinental jet, bridging Europe and America years before Boeing can even test fly the 707. Toronto becomes an aviation and business hub, initially drawing experts from Great Britain but soon from Asia, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere. Canada’s institutions adapt accordingly to the influx of talent, diversifying our nation’s economy beyond the current focus on financial services and energy.

As the title suggests, Avro Canada may have grown to Boeing’s magnitude, becoming a stalwart of innovation and progress. Conversely, the Jetliner’s unproven marriage of technology leads to innumerable technical issues and Avro goes bankrupt.

Still, consider what actually happened. Avro Canada was forced to shut down their Arrow program several years later, spurring mass layoffs that sent some of Canada’s finest minds running for the border. Many returned to the U.K. or took jobs with NASA in the U.S., leaving Canada to ponder for decades: what happened?

Taking a flier on the Jetliner would’ve probably been a better option.

References

- Requiem for a Giant — Palmiro Campagna

- For the Record — Palmiro Campagna

- The Development of the Avro C102 Jetliner— James C. (Jim) Floyd

- Jim Floyd Intervew — CBC Archives

- Our All-Out Gamble for Jet Supremacy — Maclean’s, December 1949

- First Jet Transport: Avro XC-102 — Aviation Week, November 1948