What's next for Canada's small, northern airlines?

Electric aircraft, fleet renewals, and nationwide expansions are just the tip of the iceberg.

Welcome back to The Flying Moose. Today’s article is a little different; we’re not talking about Flair or the A220 – you know, pretty much the only content I know how to make.

Instead, we’re looking at the Air Norths, the Air Tindis, and Summit Airs of the world – the smaller airlines that usually escape attention in cities like Toronto, and the ones that are actually critical to the livelihoods of entire regions in Canada.

Wouldn’t you know it – there are 3 parts to this article as well.

- Current state of air services in Canada – focusing on small airlines and building a better idea of how they work.

- What’s on the horizon – exploring the effects of aging fleets and wider market changes in Canada.

- Actions these airlines are taking today – especially those in direct response to future developments.

Current air services in Canada

The all-stars – the majors

Most people will manage to name Air Canada and WestJet – maybe Air Transat at a stretch – when you ask them to list all the airlines in Canada. Some might throw out the new ULCCs like Flair and Swoop, thanks to aggressive promotional campaigns that you can’t escape from – and no, 100% off base fares on Flair does not mean free tickets, because taxes exist.

But – unlike literally everything else on this site – these airlines aren’t the focus of this article. Despite the lingering effects of COVID, these guys and the markets they serve will probably be fine; it’s not the end of the world if, or when, one of these ULCCs bites the dust – we’ll just keep paying $400 for a flight to Vancouver like I am this July 🤡

The hidden northern network

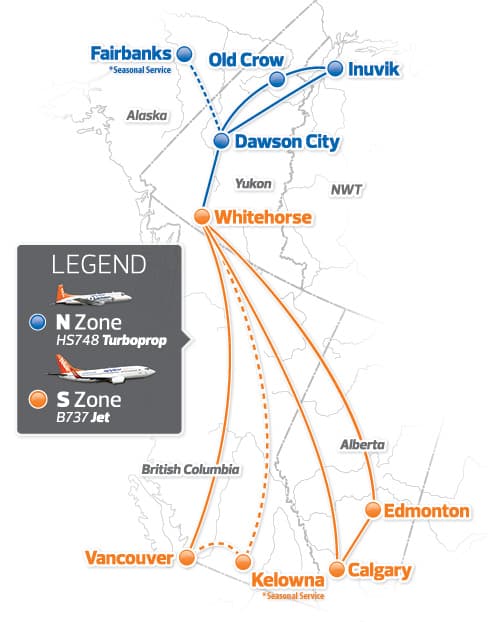

You can almost take any any airline based north of the 49th parallel and include them in this section. Ok, not exactly, but I’m talking about companies like Air North, Air Tindi, Central Mountain Air – literally anything but the ~7 airlines that fell under the first bucket. And there’s a lot more here than you’d think – take a look at this wikipedia page.

It’s hard to quantify their actual sizes, because they vary so much even within the group, but this should put things into perspective: Air North currently flies fewer than 1,000 passengers a day, compared to the 100,000 daily that Air Canada recently cleared in April. Air Tindi has 27 turboprops, while WestJet has 105 Boeing 737s.

But these airlines are critical to the communities they serve, especially Northern Canada. The North – typically defined as the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut – makes up 40% of Canada’s land but only 0.3% of our population. It’s naturally not an attractive market to serve based on sizing, making the companies that do operate here all the more important.

Air carriers in particular provide year-round access to otherwise isolated or hard-to-reach communities. The Yukon community of Old Crow is an example – with a population hovering around 200, it’s inaccessible by road and requires a flight by Air North. It certainly takes a bit of a non-profit perspective to run regular flights to a community of 200, complete with services that aren’t always optimised for yield like irregular cargo.

Another example is Wekweètì, a Tłı̨chǫ community of about 137 people in the Northwest Territories. Air Tindi serves the community six days a week ferrying things like Amazon orders, toilet paper, eggs, milk, and actual doctors.

Paul Football, a foreman with the Wekweètì community government, says that:

That’s one of the things that we depend on — this flight coming in, because we have no all season-road here.

Apart from a winter road that’s only open for around 5 weeks a year – if even anymore with the effects of climate change – air is the only year-round method of accessing Wekweètì, around 200km north of Yellowknife.

It’s this importance that resulted in $174 million dollars worth of federal subsidies to maintain air access to 140 remote communities when the pandemic hit. Individual provinces have kicked in additional money, such as Nunavut which recently approved another $22 million in March 2022 after already paying out over $100 million.

And it’s worked – sort of. Air North – seemingly the most vocal small airline on any business matter – essentially broke even post-subsidy in 2021, and Canadian North didn’t disappear – about as fundamental a success metric as you can get.

But it wasn’t pretty. Nunavut essentially funnelled public money into private companies without explaining how – saying to the public that “you have to trust us” – and Air North admitted that much of the money essentially went towards flying empty planes.

For all these airlines have gone through, the future is about to get more interesting. We’re digging into what’s coming up next – they’ll face the same challenges hitting the entire industry, but must also deal with unique challenges that we think less about. These airlines are critical to the country of Canada, and it’s something worth digging into.

What’s on the horizon

Much of what’s true today – politically and socially – likely won’t hold just several decades from now. While some changes will be more predictable than others – it’s always been true that a changing landscape opens up new opportunities.

Aging fleets

This is the arguably the most persistent issue that airlines will have to deal with. The economy booms and busts, pandemics come and go (hopefully), but fleet age can – and will – only increase. Fleets will therefore require more care and resources to maintain, just like our aging population here in Canada.

Aging fleets affect all airlines, but take a look at the average ages for some of the Northern carriers we’re talking about:

| Airline | Average age (years) |

|---|---|

| Air North | 30.6 |

| Air Tindi | 30 |

| Pacific Coastal | 26 |

| Central Mountain Air | 24 |

| Canadian North | 26.4 |

| Northwestern Air Lease | 29 |

Compare this to Air Canada or other mainline fleets:

| Airline | Average age (years) |

|---|---|

| Air Canada | 9.1 |

| American Airlines | 12.1 |

| British Airways | 13.4 |

Small airlines are dealing with fleets that are considerably older than mainline carriers. This doesn’t mean that these aircraft are unreliable – quite the opposite in a lot of cases – but it does exacerbate difficulties finding parts and expertise. In the Dash 7’s case, BC-based Viking Air is the only certified manufacturer of factory-new parts for the aircraft. This is a company in the several-hundred million revenue range, compared to the $1.8b operation of Satair that supports the life cycle of Airbus products.

What makes this situation slightly precarious is how many of these aircraft can’t be replaced easily. Models like the Dash 7 and old 737s are necessary for their combination of size, payload flexibility, and STOL or gravel capabilities. Air Tindi president Chris Reynolds said earlier last year that the Dash 7 is the only large aircraft that can fulfill the cargo and passenger needs of its route network – and that the aircraft is essentially unmatched.

It is the only large aircraft that can carry the amount of cargo and passengers of its kind to the local communities of Whati, Wekweeti, Gameti, Lutsel K’e, to Nunavut communities like Kimmirut and Grise Fiord. No other aircraft of its size can land at those communities… the performance of the aircraft is unmatched. - Chris Reynolds, Air Tindi President

Wekweeti Airstrip

Operators have turned to creative methods to keep their fleets flying. Air Tindi acquired 7 Dash 7s in early 2021, mostly for spare parts. Their Dash 7 fleet is currently projected to reliably operate for at least 1 more decade, punting the tough replacement decision down the line.

The Otter and Twin Otter are two other workhorses for which upgrades or replacements will have to be considered over the coming decades. Vancouver Island Air operates Otters that were manufactured in the 1960s – so that’s 60 years ago – and began overhauling their engines in 2019 under a new subsidiary, AeroTech industries. Among their goals? To create an “Otter Revitalisation Program” that can bring Otter airframes to “zero time”.

Vancouver Island Air’s Otters

There admittedly hasn’t been much news on the program since then – and I guess we had a global pandemic – but this is significant effort and dollars to sink into an airframe that predates the Trans Canada Highway. The mere consideration of such a program should tell you just how indispensable these aircraft have become (link). The Canadian government themselves have invested a couple of tens of millions of dollars into avionics life extension projects for the Twin Otter.

There just aren’t many manufacturers that are interested in building new aircraft tailored to the rugged Canadian context. With hometown companies like de Havilland and Bombardier gone – well, at least the aviation aspect of Bombardier – who’s really going to produce a clean sheet turboprop design for a market that might top out at 500 airframes?

It remains to be seen as to whether adequate replacements can be procured, or whether these fleets will be stuck in a stasis of sorts, perpetually maintained and upgraded like a living museum – which honestly would be pretty cool. I will say that there are a host of innovative upgrades in the pipeline – things like electric or even hydrogen propulsion conversions – that I’ll get to later in this video.

One thing’s for sure – these airlines will find a way to keep flying.

Canada is changing

We can confidently say that this country will look a lot different in 20 years, with two massive drivers of change being the effects of immigration and climate change. The former is a policy choice, while the latter is a result of poor policy choices. Factor in the myriad world-changing events that’ll inevitably happen outside of Canada, and it’s clear that aviation here will be serving a market with different needs.

I’ve picked out 2 main shifts with clear effects on aviation.

First, a growing and aging population will simultaneously stress existing hubs while creating new ones. Nearly 3 quarters of Canadians now live in large urban centres, placing pressure on major airports like Pearson to remain resilient in handling future demand. Smaller cities aren’t immune either – downtown Halifax grew by 26% between 2016-21, the fastest downtown growth rate and easily outstripping Toronto’s 16%.

This period from 2016-21 saw impressive population growth in downtowns (11%), and similarly impressive growth in suburbs far away from downtown (9%). If this sounds paradoxical, it’s because everywhere is growing all at once.

Even if Northern populations don’t see such meteoric growth, connections with these urban centres will only increase in importance. Carriers hitherto focused on remote areas may eventually need to pay greater attention to links with growing hubs like Calgary, if for no other reason than to capture the upside of population growth.

first flight :^)

Air North did exactly this just several weeks ago, launching the first direct scheduled flight between Yellowknife and Toronto. This has implications for revenue models, fleet management, and talent – but it’s a necessary consideration if players don’t want to cede the benefits of growth to the Air Canadas or WestJets of the world.

The second shift is how Canada’s air-dependent industries will likely change, driven by a multitude of factors but chiefly climate change. I’m talking primarily about mining and fossil fuel extraction, activities that make up a healthy amount of flying for airlines in remote regions.

Exact numbers are difficult to come by, but there are a plethora of dedicated charter operators serving the oil and gas industry. This comes alongside the mining-related activities explicitly outlined in the charter services offered by players like Air Tindi, Air Nunavut, and Central Mountain Air. Flying is often the only effective way to reach remote extraction sites, especially when needing to move entire mining crews.

Apart from charters to job sites, fossil fuel extraction requires other extreme sports like pipeline patrols. Ok, not exactly an extreme sport, and not really airline work, but still impressive nonetheless. Pilots hop into tiny Cessnas and skirt the nearly 1 million kilometres of fossil fuel pipeline we have in Canada – just 1,000 feet above the ground while dodging power lines and wind turbines. They snap photos and note down egregious violations of normalcy like people literally stealing oil.

The Pilatus PC-12, a truly very good looking aircraft

A net-zero future won’t have room for fossil fuels, and mining will shift towards rare earth extraction. This won’t completely upend the charter operations of Northern airlines, but use cases will be different. Instead of flying large mining crews on a 40-seat Dash 8, charters may now only require a Pilatus PC-12 to ferry individual wind turbine inspectors to remote fields; the latter being a situation that doesn’t require large crew to regularly travel far.

The effects of a changing environment will affect Northern airlines more than just through routes and mission sets, so much so that we’ll give it its own section.

The race to net zero

We’ve covered the changing nature of route networks and mission sets, largely due to population and industry developments. But there’s an operational aspect that airlines will have to deal with – and that’s becoming net zero.

This is the elephant in the room for any airline talking about the future. Going net zero will be difficult enough for anyone, but doubly so for Northern airlines that rely on old but still more-than-adequate aircraft.

This ties in what we discussed earlier. Northern airlines regularly take on smaller-capacity missions in cold climates, using gravel runways, or needing STOL capabilities – naturally a small market that hasn’t attracted new aircraft development in decades. The best aircraft for these missions therefore tend to be 50-year old designs that are inherently less fuel efficient, like early 737 models, somewhat unfairly increasing the pressure to adopt cleaner technology despite a minuscule footprint in absolute terms.

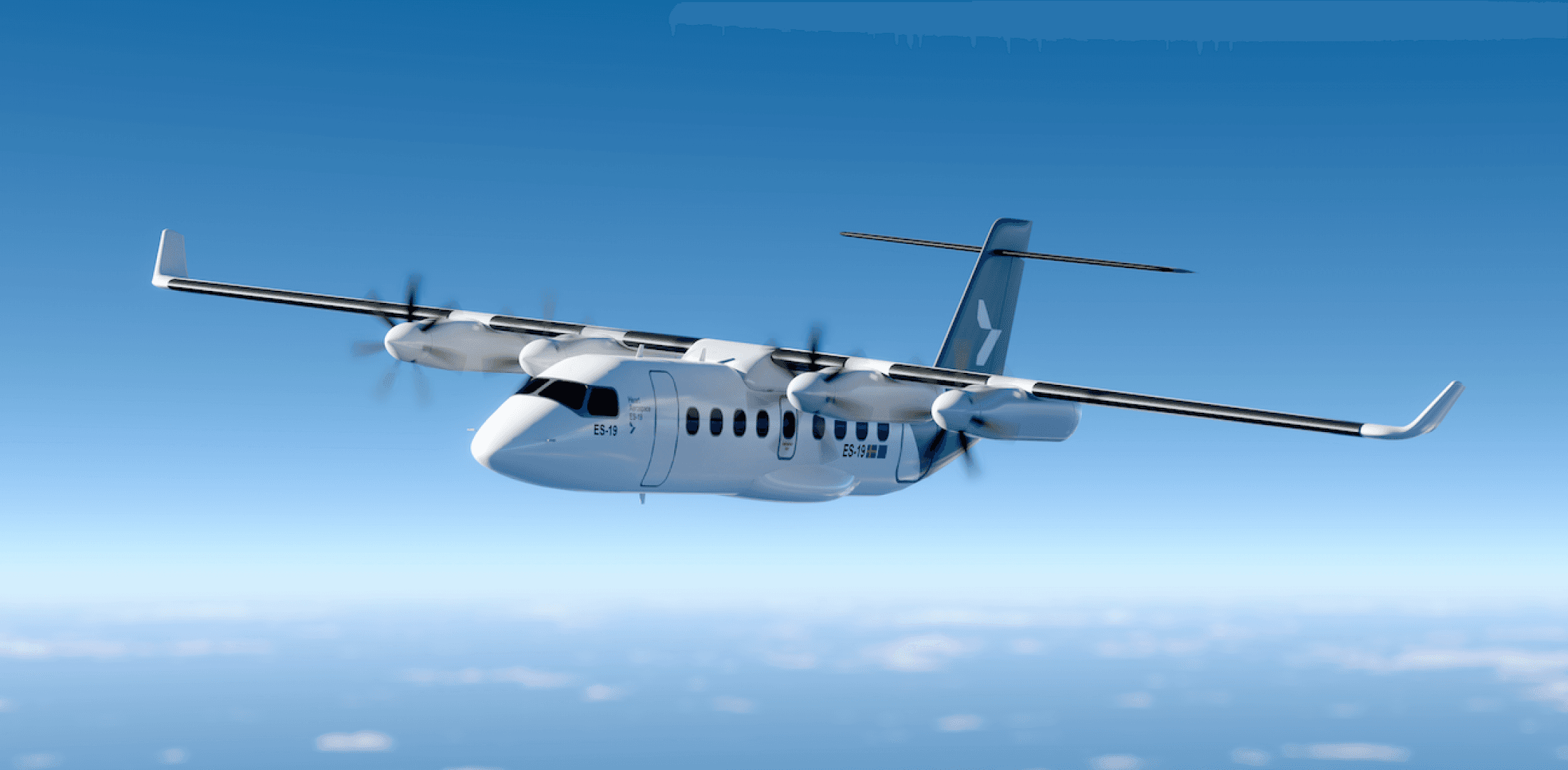

It does help that advances in clean aviation have hitherto trended towards regional aircraft that could fit the use cases found in Northern Canada, just by nature of it being easier to develop short-range aircraft than intercontinental ones. Models like Heart Aerospace’s ES-19 – an electric 19-seater – could slot well into the fleet of Central Mountain Air, for example, replacing the Beechcraft 1900.

Heart Aerospace ES-19

Yet the 1900 boasts superior performance often critical to missions in the North, namely with STOL capabilities and the option to operate from grass or gravel runways. We don’t know much about the ES-19 yet, but something tells me it’ll be a little less rugged – if anything, Heart’s electric airliner will only fly 400km, far less than the near-1000km range of the 1900.

Airline actions

While things will clearly change – in more ways than discussed – these airlines aren’t standing idle, waiting for things to happen. Many are on the offensive, and we’ll see some of the impressive ways that small carriers are building for the future.

True innovation

If the future will be fundamentally different, why not try something fundamentally new? Instead of chasing incremental upgrades, some airlines are trying to crest the wave of change and create tomorrow – instead of trying to catch up.

We’ve established that this market is naturally less attractive for large manufacturers, but some groups are circumventing the titans of industry and placing innovation straight into the hands of small airlines. With regards to the environmental trends we covered just now, major strides have been made in pursuit of zero-emission propulsion systems, with exciting developments regarding the Dash 7 and de Havilland Beaver.

Air Tindi recently announced their participation in NASA’s Electrified Powertrain Flight Demonstration (EPFD) project, a program intended to demonstrate the commercial viability of such technologies when applied to existing aircraft and operated by real airlines. By contributing to flight testing and lending expertise to overcome technical barriers, the hope is for the EPFD to accelerate the adoption of electric propulsion aircraft.

Air Tindi is doing its part by supplying a Dash 7 from their fleet, working in concert with Seattle-based electric propulsion manufacturer magniX and service provider AeroTEC to create a hybrid electric airliner. The retrofitted Dash 7 will feature 2 standard Pratt & Whitney PT6 engines alongside 2 magni650 electric propulsion units produced by magniX. News of this broke in April 2022 and no entry date into service has been announced yet, but this is real work being done by Air Tindi, not some ESG report stuffed with recommendations that’ll never see the light of day.

And there’s good reason to believe that this hybrid will work, because magniX has experience retrofitting electric planes that actually fly – with another small Canadian airline. Harbour Air is deep into a partnership with the same magniX to certify a fully electric version of the dHC Beaver, appropriately named the eBeaver – very cute name. The eBeaver first flew in December of 2019, just 9 months after Harbour Air launched their retrofit program, and is instrumental in their plans to operate an all-electric fleet of over 40 aircraft.

COVID and the resulting supply chain issues have unfortunately complicated initial plans to certify the type by 2022, with forecasts now set for mid-2024. A large portion of taking a single demonstrator eBeaver through to production hinges on Swiss battery company H55 and several Chinese electronic components, which – by nature of involving Switzerland and China – means that progress is now at the whims of whatever international backlog you see on the news.

Still, Air Tindi and Harbour Air are two airlines that are actively taking steps to future-proof their fleet. It’s commendable that these commitments are coming from smaller players without deep financial resources or political might, and their proactivity gives larger airlines an exemplar in spirit at the very least.

Building resilience

While moonshots are exciting, and arguably necessary to truly get ahead in the future, they don’t always go to plan. Actually – they rarely go to plan. This isn’t to say that hydrogen or electric aircraft won’t work out – they probably have to work out in order for us to hit net zero – but it’ll probably take longer than expected.

In the interim, Northern airlines are also bracing for the future by fortifying their existing assets, building resilience with more conventional, well-understood methods. In the face of aging fleets and changing demand patterns, areas we explored earlier in addition to changing climate demands, airlines have begun to de-risk. They’re strengthening both their current fleets – in a physical sense – and strategic positions – in a financial sense.

Fleet resilience is the easiest to spot, and the examples we covered earlier illustrate this well. Air Tindi’s recent orders for 7 Dash 7s worth of spare parts and Vancouver Island Air’s Otter Revitalisation Program are just some ways that airlines are future-proofing existing assets. Central Mountain Air announced this May that they’re adding another Dash 8-300 to their fleet, one that will be upgraded with – this is a mouthful – ADS-B and LPV capabilities.

Apart from building up physical reserves of parts and aircraft, some airlines have opted to build resilience through financial strength. The 2019 merger between Canadian North and First Air is a prime case of 2 companies shoring up their finances by joining forces, instantly vanquishing competition from the other player while creating opportunities to take advantage of operational and network synergies; also don’t forget that “operational efficiencies” conveniently describes the layoffs that tend to follow these things.

The literature is split on this topic – likely based on which company funded the study – but there are plenty of examples from industry of layoffs following mergers as redundancies are intentionally cleared out. Canadian North staff also voiced concern in late 2019 that the merger felt more “like a First Air takeover, not a merger”. Airline mergers are always tough because so much of the industry is based on seniority and service time, leaving no easy answer for the combination of 2 distinct sets of rankings.

Either way, the merger creates a more stable airline that is better prepared to weather the vagaries of the airline industry. The pandemic tested this resilience immediately, and there’s no telling whether two independent Canadian North and First Air companies would’ve survived otherwise.

Not every airline is in a position to merge or acquire other company, so smaller-scale partnerships also help build this collaborative resilience. Air North has been the most active on this front in recent memory, finalising 2 interlining agreements this year with Philippine Airlines and Air Transat. Although not as strong as a true alliance or partnership, the ability to fly both airlines on a single ticket only adds to the appeal of Air North’s services – and it’s an upgrade that doesn’t require a substantial physical or financial investment.

Moving mainstream

Finally, there’s the standard stuff. The actions that are necessary to keep airlines relevant today, actions that aren’t loud or even particularly forward-looking. There’s a lot of work to be done in maintaining existing services, and some smaller airlines are handling current market forces by drawing inspiration from mainstream carriers.

Air North has come up a lot in this video, and for good reason – they’re one of the more active Northern airlines, recently opening up the first direct flight between Yellowknife and Toronto in May of this year. With momentum from the COVID recovery and increased appetite for travel – oh yeah, you’ve seen the lines at Pearson – opening a route between Yellowknife and Toronto makes sense. It’s this kind of “mainstream” decision that smaller carriers are increasingly undertaking. It’s a decision that comes with risks, but it speaks to their comfort with acting like a larger player in response to current conditions.

Air North has also quietly reshuffled their executive team to place a greater emphasis on cargo, creating a new VP of Cargo and Airport Ops in early May. Critically, this consolidates the Scheduled and Chartered businesses under one VP, showing just how important cargo will be moving forward. This is a market trend that’s already prompted WestJet and Air Canada to start building fleets of dedicated freighters; I made a video on this topic around a year ago – check it out here! Air North likely recognised the looming growth of freight, especially in a geography where air cargo is already critical – and have followed larger players in doubling down on cargo.

Sticking with cargo and Yellowknife, Buffalo Airlines purchased their first jet in April of this year, a 737-300SF. The move was necessary to meet increased demand for next-day delivery, both through their own Buffalo Air Express courier company and to fulfill FedEx, UPS, and DHL contracts. Although not unprecedented, it was still jarring for a company that had hitherto relied on WW2-era C-46 Commandos for cargo, and a clear indication of a willingness to move towards the status quo.

Both Air North and Buffalo Airlines offer examples of small airlines following the lead of mainstream players. This isn’t a knock on smaller carriers – their needs are almost always different from the Air Canadas and WestJets of the world, and it takes time for their markets – for example in Yellowknife – to act like larger metropolitan areas. It’s always interesting to see how changes filter through particular industries, and these small airlines – among others – have demonstrated that they’re more than capable of responding to market forces with the same vigour as larger players.

In conclusion

So what does this all mean? If there’s one thing I wanted you to take away from this video, it’s this: small airlines are more important than most people realise, both for serving current communities and for driving innovation.

Despite their small size, these carriers are doing much more than the majors to spur advancements like electric propulsion. This’ll be critical as Canada continues to evolve, and it might be the little guys that pave the way forward.